In pre-Highway 101 days, the city of Ventura's neat grid of streets ended, at its southern point, at the ocean.

Getting to the beach from midtown was as easy as from downtown, and you didn't mind the short walk because it was the less fortunate people who lived nearest the water.

Then in the 1950s came Highway 101. The neighborhood known as Tortilla Flats was dismantled, and Chestnut, Fir and Ash streets dead-ended at the freeway. California Street became a narrow offramp, and the result was a large part of town separated from the beach.

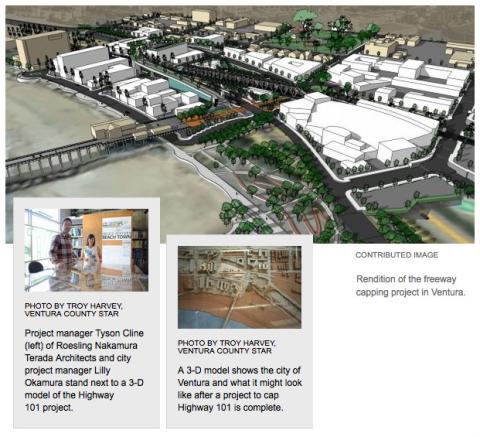

Returning Ventura to what it was like before the highway split the town is at the center of an ambitious project to cover the freeway. Known as the "freeway capping" project, the idea is to roof over the freeway with asphalt, creating a tunnel three blocks long for highway motorists.

On top of it, a conference center, a transportation hub for trains and buses, and a mix of retail and commercial uses would go up.

Streets that now stop at the freeway would extend over it and a new road running alongside the ocean would give motorists greater convenience in flitting between downtown and a lively beachside strip.

"To be able to reorganize and restore the urban fabric that we used to have would be unbelievably huge to the city in so many ways I can't even count them," said Bill Fulton, the former Ventura mayor who now is vice president of Smart Growth America, a Washington, D.C., urban planning think tank. "The question is, if we can pull that off."

Ventura's situation mirrors that of cities throughout the state. As populations grew, planners who organized freeways sought a direct path, rather than worrying about keeping neighborhoods intact.

"Caltrans was motivated by moving cars as far as they could from one region to the next," said Tyson Cline, project manager of the capping project. "They were charged with moving cars."

So cities are moving to correct what are now deficiencies, he said.

The Southern California Association of Governments gave Cline's firm, Roesling Nakamura Terada Architects, a $160,000 grant for the project, said Lilly Okamura, a senior project manager with the city.

"SCAG pays the consultant team directly, so the city isn't involved in the funding pass-through," Okamura wrote in an email.

Cline's firm developed what it's calling a "concept" for the project, since Cline and others say it's too soon to refer to the efforts as full-blown plans.

Early estimates put the project's cost at $400 million. City Community Development Director Jeff Lambert cautioned against making much of that number.

"There's too many unanswered questions to come up with a price that's really useful," he said.

Whether the freeway would have to be further depressed, what structures would be ultimately included, and even what decade it would be built in would all affect the cost, Lambert said.

"It really is possible if we break it into bite-sized pieces," he said. "If we don't dream, we'll never get there."

While Ventura's project could span two or three blocks, plans to cap Highway 101 in the Los Angeles corridor include a mile of freeway. Called Hollywood Central Park, the $1 billion project would go from Hollywood to Santa Monica boulevards — a total of 44 acres.

This summer, Friends of the Hollywood Central Park will commission an environmental impact report, which will give everyone a better idea of the plan's feasibility and true costs, according to Laurie Goldman, president of the group.

The city of Los Angeles, along with a private donor, are covering the costs, she said.

"Yes, it's expensive," Goldman said, "but I look at it from the other side: What does that hefty price tag get?"

Not only would there be open space in the middle of the city, but also land values would increase, tourism would go up, jobs would be produced and the project would encourage healthier lifestyles, she said.

Unlike Ventura's capping project, Hollywood Central Park would be mostly a linear park in the style of the High Line, a greenbelt constructed on an old freight rail line above the streets in New York City. Still another project would cap downtown L.A., from Hope and Alameda streets. Planners peg that half-mile project at $700 million.

Ventura's is the smallest of those three ideas, and would include a small linear park on the Chestnut Bridge southbound onramp.

But before the local capping project gains any real traction, plans to move the offramp from California Street to Oak Street must be made, Fulton said.

That project is on hold as the city waits for federal dollars to be freed up, Lambert said, adding that he hopes but doesn't expect it to get built in 2013.

Then there will be further discussions with Caltrans, Union Pacific Railroad, the community and others.

Meanwhile, people must organize, Fulton said.

People fall into two traps with this project, Fulton said: those who see it as a "pie in the sky" idea that will never happen and those who will sit back and wait for what they see as an inevitable part of Ventura's future.

Neither camp is right, he said.

"You have to be very proactive and aggressive in making this happen," Fulton said. "It's a complicated, expensive thing to do."

For several weeks, a 3-D version of the plan was displayed at Ventura City Hall along with comment cards. Those who commented mostly approved of the project but others worried it would bring congestion and block views.Residents who are worried about Ventura turning into an unmanageable beach town needn't worry, Fulton said.

This is not just about tourism, Fulton said, but "about restoring the heart of our community so it's a very wonderful and compelling place to live."